|

Rheinheimergenealogypages

including Reinhard, Rheinheimer, Shively, and Stout |

The Schlappach and Eckell Family in Ohio, Switzerland, and Germany

This history starts with three girls orphaned in Ohio in the middle of the nineteenth century. They are Anna Albertina, known as Tena, Mary Adaline, and Johanna Benjamina, known from an early age as Hannah. They were born and were living on a farm in Rose Township, Carroll County, Ohio, and were 16, 13, and 10 when their father, John Slabaugh, died in June of 1852. Their mother, born Maria Eckell, had died two years previously. We don't know what happened to them immediately, though they may have been taken in by the Schaeffers, nearby farmers. The Carroll County, Ohio, probate court record from one year later says "In the matter of the heirs of John Slaughbaugh. On this fifth day of July, Albertina Slaughbaugh, aged sixteen years, on the seventh day of March, in the year one thousand eight hundred and fifty two, and Adaline Slaughbaugh, aged fourteen years, on the thirtieth day of August, in the year aforesaid, minor heirs at law of John Slaughbaugh, deceased, appeared in open court and made choice of Peter Schaeffer for their guardian, which choice was approved by the court: And also, at the same time, on application made, the court appoints the before mentioned Peter Schaeffer as guardian of Hannah Slaughbaugh, aged twelve years, on the thirtieth day of September, in the year aforesaid, also a minor heir at law of the said John Slaughbaugh, deceased. And it is ordered by the court, that the said Peter Schaeffer enter into bond according to law, in the sum of three thousand five hundred dollars, with James Beatty and Valentine Rinehart as sureties." Schaeffer farmed nearby, and Rinehart and Beatty were farmers up the road, one in either direction. Besides the neighbor relationship, we don't know if there was any specific tie, for instance through church, between the Schaeffers and Slabaughs. They likely were not family. In December 1850, a few months after the death of his wife, John Slabaugh had sold seven acres in the southeast corner of his property for $125 to Samuel Burwell. In 1854, Peter Schaeffer sold the rest of the property on behalf of Tena and his two wards to Burwell for $2368. Tena was no longer his ward as of a week previously-- she married George Shively, who had grown up ten or fifteen miles north of the Slabaugh farm in Stark County, shortly after her eighteenth birthday in March, 1854, and the sale of the farm occurred one week later. It is typical in the records for an official to ask the wife separately whether she's on board. That might have been especially important in this case. Justice of the Peace John Hays, after he asks Tena and George if they approve of the sale, records this: . . . the said Albertina being examined by me separate and apart from her husband and the contents of said instrument being made known to her by me she declared that she did voluntarily sign seal and acknowledge the same and that she is still satisfied therewith. Hannah, shortly after her 14th birthday, petitions the court to change her guardian to George Shively, moves to Kosciusko County, Indiana, with George and Tena in the late 1850s, and eventually marries George's younger brother, Daniel. Mary Adaline also moves west and eventually marries Phillip Seneff in Marshall County, Indiana at age 28.

In addition to the proceeds of the farm sale, the girls split about $1200 worth of gold received via a German-language bank in Cincinnati from a law firm in Cassel (now Kassel), Germany. Where did that come from? And how did John and Maria get the farm in the first place? Ohio became a state in 1803, so it wasn't the frontier, but it wasn't quite "settled", either. This is the eastern edge of Tecumseh territory, and for all of the Northwest Territory, the plan on the part of the young government of the United States was to move the Native American population westward and raise money by selling land to incoming settlers. At the time of the founding of the state, one could buy not less than 160 acres at two dollars per acre. A financial crisis in 1819 changed the rules; farmers could sell back 80 acres to the government to help pay the bills, and land prices dropped to $1.25 per acre. Eighty acres became the standard size of a plot of farmland, and this is what John Slabaugh bought from John Oswalt in 1834. It was "the west half of the northeast quarter of section seventeen, township sixteen, and range seven", in Rose Township, Carroll County, Ohio. Although Johannes didn't buy his land directly from the US government, the description tells us it was part of the first territory surveyed and set aside for sale. Sections were a square mile (640 acres), townships were numbered before they were named and aligned with north/south ranges one through seven on the Ohio side of the Ohio/Pennsylvania border.

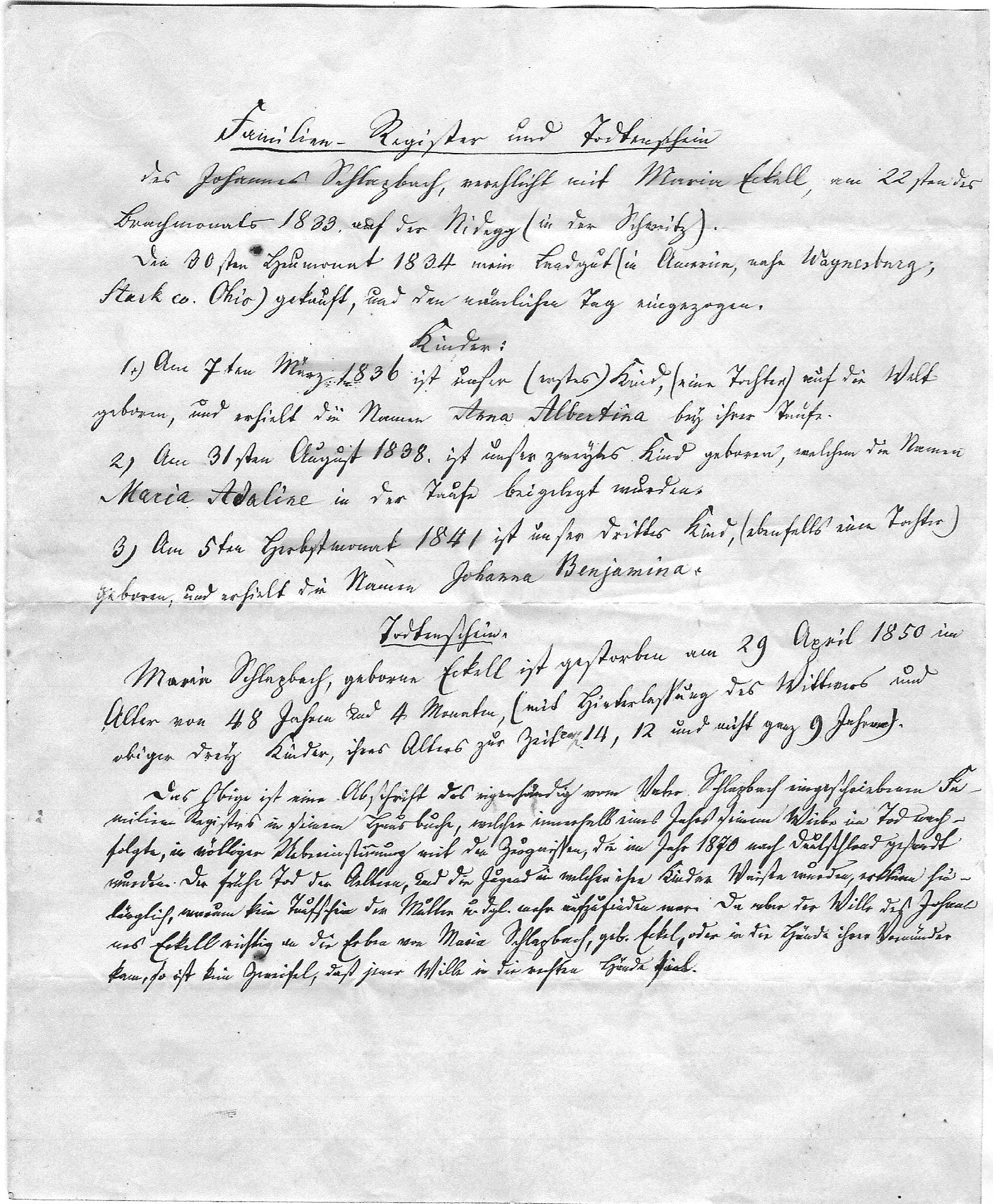

John Slabaugh saw his name spelled Schlapbach, Slaughbaugh, Slaybaugh by his daughter, and spelled it Schlagbach himself in the family record he kept, which records the birth of his three daughters and the death of his wife, but he was born Johannes Christian Schlappach in Oberlangenegg, Switzerland in 1796. The family name in Switzerland in the twenty-first century seems to be spelled Schlapbach. Family lore says he was born in France and fought in Napoleon's army. This is unlikely but possible--his marriage record says he is Johannes Christian Schlappach of Oberlangegg, near Schwarzenegg, but we did not find his birth record there, though the Schlappach family was well-represented in the area at that time. As for fighting with Napoleon, it's a possibility. The Swiss are famously neutral, but not in Johannes' day, or at least not until after the Napoleonic Wars--Swiss neutrality was recognized at the Treaty of Paris in November 1815. The French Republican Army invaded and defeated Bern in 1798, and as a part of the French Empire under Napoleon, Swiss troops served in the Grande Armee that invaded Russia in 1812. Johannes would have been 16 years old then, but it's unlikely he took part in the Russian campaign--of the 8000 Swiss foot soldiers who took part, only 300 returned. He might have been conscripted for the final battles of the Napoleonic Wars, however, concluding with the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Johannes would have been 19, and, by this time, upon Napoleon's return from Elba in 1815, the Swiss were fighting against Napoleon, not for him. We don't know if participation in any of the late Napoleonic battles is really a part of Johannes Schlagbach's story, or where he was or what he was doing before 1833, when he and Maria Eckell were married on 22 June, 1833, at the Nydeggkirche, completed in 1346 and still in use in the old city section of Bern.

Maria is the one with the connection to Cassel. Though she was probably born in Switzerland, her father, Johann Benjamin Eckell, was from Cassel. He was born in 1756 and moved from Germany to Switzerland sometime probably in his twenties or thirties. We know what little we know about this because Maria's brother, also named Johann Eckell, wrote a letter in 1810 describing a trip he took to Cassel, a copy of which survives. Before we get to the letter, it's worth noting that Maria's youngest daughter Hannah is really Johanna Benjamina, named presumably after her grandfather, and the letter mentions a brother (so Hannah's uncle) Benjamin as well. The 1810 letter is addressed to "Dear Pastor" in Bern, Switzerland, but came at some point into the hands of Maria and with her to Ohio. We have a transcribed German version (with a bit of French), and a transcribed and translated English version. In the letter Johann lets his pastor know about his travels, how things went when he met his father's family, how he's getting along in Cassel, but most importantly he wants permission from his father to marry, or proof of his father's death--his mother died earlier--so that he can marry on his own.

The letter, being written by a common person over 200 years ago, is interesting on many levels, and it also reminds us of the state of the European continent in the time of this set of ancestors. In 1810, Napoleon was in busy in Spain and Austria, but had defeated and redefeated much of Europe and installed family members as the heads of state in various places. In pre-Germany in 1810, his brother Jerome was head of the Kingdom of Westphalia. The Kingdom in this form only existed from 1807 until 1813, but during that time Cassel was the capital, with Jerome Bonaparte, married to German princess Catherina of Württemburg, in charge. Johann Eckell arrived as an apprentice cabinetmaker, and Jerome and friends were spending a lot of money (to Napoleon's annoyance) sprucing Cassel up to imperial standards, so 1810 was a good time to arrive. Additionally, arriving from Switzerland, Johann spoke French as well as German, and it's clear from his letter that this facility at least as much as his woodworking skills secured him a position at the theatre. He must have done well for himself, however. A copy of two other letters, this time sent to Maria and dated December 1825 and March 1826, survive. By this time Johann had been established in Cassel for fifteen years and signs the longer letter master cabinet maker Eckell. The first letter sends the key to a chest sent separately at Christmas 1825 and the second is asking whether Maria had gotten the money he'd sent and why he hasn't heard back yet.

Maria had two other brothers, Benjamin and Fritz, mentioned in the two letters. The family seems to have lost contact with Fritz by 1826, but

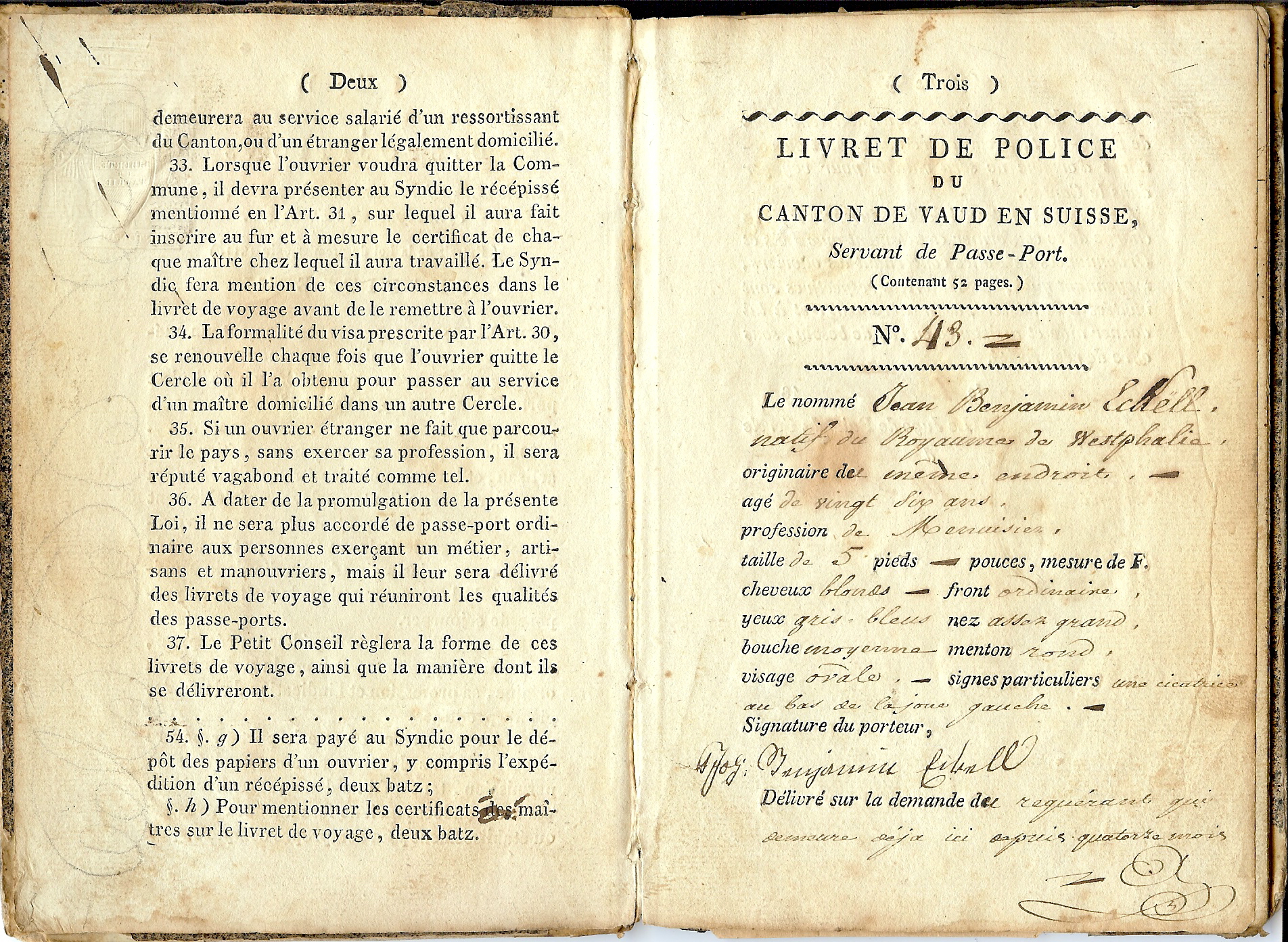

we know a little bit more about Benjamin, thanks to the efforts of Rebecca Carrington and Anne Whiteside. A copy of his

Swiss passport from the years 1812-1833 survives,

according to which he was born Johann Benjamin Eckell in Germany in 1786, is a carpenter, is five feet (five feet three or four inches in current feet) tall,

has blond hair, gray-blue eyes, an oval face, medium mouth, round chin, quite large nose, and a scar at the bottom of his left cheek--that is what

passes as a passport photo in 1812. However, having no illustrious ancestors who had portraits made, that is the best physical description we have of

anyone on this site before the invention of the camera a couple of decades later.

By 1835, Benjamin was in Stark County, Ohio. He was naturalized on 5 September 1840, and the requirements at the time were that he had lived in the state for

one year and in the United States for at least five years.

Politically, many entities are trying to figure themselves out in the years after the end of the Napoleonic wars. In Switzerland, the system of federated Cantons only went away for a short time during French occupation around the time Maria was born, but the what and how of the Cantons, both within and between them, was very much contested during the time Johannes and Maria were growing up separately in Switzerland. The main points of contention were separation of church and state--i.e. wanting to practice Catholicism in a Protestant Canton or vice-versa, and political power and representation of the cities versus the countryside, which generally had more people and less political power. Maria and Johannes would likely have not been bothered too much by the church and state issue, both being Protestant in a Protestant Canton, Bern, but would have been on opposite sides of the latter question. Maria came from a family of artisans in Bern, the city, while Johannes was a farmer from the Berner Oberland. Bern was not an epicenter of conflict, but Basel, for instance, split into two Cantons, Basel the city and Basel the countryside, in 1833 after not just diplomatic discussions but actual battles. We don't know the specifics of a decision to relocate to Ohio in 1834, for either Johannes and Maria or for Maria's brother Benjamin, but we do know Switzerland was contested and Ohio was being marketed, at least, as cheap and easy and wide open.

Moving northward and back in time, we want to acknowledge the kind help and local knowledge of Heinz Klippert, genealogist of the Schwalm and distant cousin. The 1810 letter indicates the elder Johann Benjamin Eckell (1756-~1810) moved from Cassel, but his son Johannes finds his father's brother in Zwesten, known today as Bad Zwesten--"Bad" is German for bath, and the use of the prefix indicates Zwesten is now an official spa town with a naturally-occuring mineral spring. We have more work to do on the Eckells. We don't know the name of Maria's mother, and so far all we know about her paternal grandfather, Hans Johannes Eckell (1707-1779) is that he came from Frankenberg and married Maria's grandmother Elisabethe Keller (1712-1761) in Zwesten in 1729. Elisabethe, however, was a local girl of the Schwalm. Her family names, besides Keller, include Eiler, Gluntzer, Hoos, Huck, and Stroh, all of whom are well-represented in the area today. They are from villages south of Zwesten along the Schwalm and its tributaries--Gungelshausen, Niedergrenzebach, Ransbach, Riebelsdorf, Röllshausen, Salmshausen, Steina. To give a sense of scale, one can walk from any one of these villages to any other in under about an hour.

The earliest ancestors we can trace were born in the area around 1550-1580. See the map for birthplaces and dates. Heintz Gluntzer is the earliest we know by name-- he died in 1610 in Gungelshausen. The Kellers were in Salmshausen for generations, the Gluntzers in Gungelshausen, less than two miles away, the Strohs in Röllshausen, a mile in the other direction, the Kauffmans in Zella, and the Eilers and Hooses in Steina, a solid four miles downstream on the Schwalm. The first "outsider" we know of to marry into this family was Anna Martha Huck (1665-1698), who immigrated from Densberg, a full twelve miles away, to marry Johan Niclas Hoos (1666-1699) in 1686. Even Hans Johann Eckell(1707-1779), who moves the family up to Zwesten when he and Elisabethe Keller (1712-1761) marry in 1729, was born only 24 miles away in Frankenberg. Two quick generations later, however, our ancestors were first in Switzerland and then in Ohio.

Life was not easy in the Schwalm river valley during this period, about 1600 to 1800. Being a river valley, it was prone to flooding. One note in the parish record book notes the river had reached the smith's house in Salmshausen in July of 1619. Plague was recurring. Our ancestors Clos Kauffman and his wife both succumbed in May of 1612, and there was a large outbreak starting in October 1635. So many people, of all ages, died that some of the death records list "not of the plague" as the cause of death. In Gungelshausen, the household of Johannes Gluntzer (1603-1667) and Margretta Daub (1603-1636) was badly affected. They had lost an infant son in 1626, but had four children ranging in age from nine years to six months at the beginning of this round of plague. The baby, Catarina, died first, in November. Margretta died at age 33 in May, and the two middle children, Johannes, age 7, and a daughter whose name is not recorded, age 6, were two of the last victims of this round of plague in August and September, respectively, before it receded at the end of summer of 1636. Only the father Johannes and the eldest child, Gelasia, who went by Gela, survived. Johannes remarried a couple of years later, but had no more children. Gela--we wouldn't be here without Gela--married Helwig Keller (1621-1703) and died in 1714 at the age of 87. Gela named three of her sons Johannes, known as the eldest (1651-?), the middle one, and the youngest. She may have been thinking of her father, but she wasn't doing her genealogist descendants any favors. As if flooding and plague weren't enough, the Thirty Years War took place from 1618-1648. The war had religious roots in tensions between Catholics and Lutherans, but also a significant political component, especially as the war continued and more political entities got involved. Estimates of deaths from battles, disease, and famine throughout what is modern Germany vary, but could have been up to 50% of the population in a few regions. Our ancestors were Calvinists under Landgraf Moritz in 1618--the population was considered to be of the same faith as the king, or landgraf in this case. There's independent evidence that the family was Protestant in that many of them have confirmations recorded at the local churches at age twelve or thirteen. Calvinists were generally on the side of the Lutherans--the Schwalm river valley is only about forty miles from Eisenach, where Martin Luther translated the New Testament into German--but only because the Lutherans had a bigger argument with Catholics than with Calvinists. The largest battle in the Schwalm took place in November of 1640, the Battle of Riebelsdorf Mountain, with the Protestant forces turning back a significant Imperial (Catholic) incursion into Hesse. In advance of the battle, the Imperial forces burned down the villages in the area, including Ransbach, Steina, and Salmshausen. According to a history written for Museum of the Schwalm in Ziegenhain, Ransbach alone was burned down three times during the course of the Thirty Years' War.

The available birth, death, and marriage records don't mention the war directly. Instead, what we see are an occasional entry like this: Hans Kauffman of Zell was shot by Poles 2 August 1636. This might have been in a battle, but more likely not--he was probably in his forties. More common are marriages of local women to soldiers, and most common of all are births of a "soldier-child" to local women. We didn't find any of these three categories in our direct family line, but they are certainly in the extended family in the Schwalm.

Hesse-Cassel, where this part of the family is located, came out of the Thirty Years' War and the Peace of Westphalia ending it in good political shape, but in not very good financial shape, what with all the towns being burned down and soldiers having to be paid to burn down other people's towns. Continuing with the political theme for the years 1600-1800, Moritz' daughter-in-law Amalie Elisabeth held things together for her eight-year old son William VI after her husband William V had lost most of the territory of Hesse-Cassel and died after fleeing Cassel with their heir but without their daughters. Amalie Elisabeth gets a lot of credit for managing generals and politics and income for the Landgraviate in a time when the belongings of women were generally seen as acquisitional opportunities for men. She also introduced the rule of primogeniture, meaning the heir inherits all, rather than splitting things up among heirs, which is likely a good thing because her grandson Charles I and his wife had twenty-four children in twenty-five years (1674-1701), fourteen of whom lived long enough to be named. Charles introduced the practice of renting soldiers out to other states when Hesse-Cassel didn't have a stake in the outcome, a practice that may have impacted our family a couple of generations later. Charles' son Frederick succeeded him in 1730, but only after Frederick had been King of Sweden for ten years, having accomplished that by virtue of marrying the future Queen of Sweden. Under the reign of King Frederick, science has developed – he never bothered to read a book. The merchant business has flourished – he has never encouraged it with a single coin. The Stockholm Palace has been built – he has never been curious enough to look at it. Frederick was succeeded in Hesse-Cassel by his brother, William VIII. Hesse-Cassel saw another major war under William VIII, this time of only Seven Years, but significant nonetheless. This war is known as the French and Indian War in the United States, but is also known as the first world war, with engagements in Europe, North and South America, the Philippines, and India. We round out our overview of the political leadership of Hesse-Cassel in this era with the son of William VIII, Frederick II who both supported George II of England, his brother-in-law, against Catholic Charles Stuart in the Jacobite rising of 1745 and broke with a long Calvinist tradition by converting to Catholicism. Later he provided--this had become something of a staple of Hesse-Cassel finances--troops for his nephew George III's war against the revolutionaries in North American, so many that all German troops in that conflict came to be generically known as "Hessians".

Returning from the royal family to our family, Anna Stroh (1650-1693) married Johannes Keller the eldest(1651-?) as her second husband in 1677, her first having died shortly after their marriage in 1673. Their son Johann Helwig Keller (1678-?) also married twice, first to the miller's daughter in Riebelsdorf, Anna Barbara Eil, or Eiler, in 1704. They had three children--briefly. Johann Helwig kept the mill but lost his first family--his wife died in childbirth along with their third child in 1711, and the other two children, Anna and Johann Helwig, died at ages 5 and 8, respectively, in 1713 and 1714. Johann Helwig the elder had remarried six months after his first wife's death to Anna Hoos (1690-1723). Anna's father, Johann Niclas Hoos (1666-1699) had been a tanner in Steina and her mother Anna Martha Huck had been a miller's daughter, but both were deceased at the time of her marriage, having died (her father) when Anna was eight and (her mother) when she was nine. Johann Helwig and Anna had only one daughter, Elisabethe Keller (1712-1761), whom we've mentioned before--she married Hans Johann Eckell (1707-1779) in Zwesten. Elisabethe and Hans Johann had thirteen children, the youngest of whom was born Christmas Day, 1756. This was Johann Benjamin Eckell (1756-~1810) Maria Eckell's father. We conclude this history with some speculation. We don't know why Johann Benjamin moved to Switzerland--the only connection we could find is that his elder brother Melchisedeck Eckell (1734-1755) died in Zurich. However, Johann Benjamin went to Bern, and Melchisedeck died at age 20, a year before Johann Benjamin was born. The timing suggests another reason to leave town. In 1776 Johann Benjamin turned twenty. Of the 12,000 troops from Hesse-Cassel sent to fight for the British in North America, some were volunteers, but many were not. Maria Eckell may have wound up in Ohio in the 1830s because her father avoided being sent to New England in the 1770s.

This site powered by The Next Generation of Genealogy Sitebuilding v. 14.0.2, written by Darrin Lythgoe © 2001-2025.

Maintained by Randal Rheinheimer.